Deep-Sea Minerals Could Help Power the Global Energy Transition

Introduction:

Renewable, clean, energy has become one of the defining technological priorities of the modern era, with both governments and private industries continuing to invest billions of dollars annually in this space, to accelerate the transition away from fossil fuels and toward cleaner, electrified energy systems. Electric vehicles signify this transition best, as they were once considered speculative; and now they are manufactured at scale, while advances in battery technology and grid infrastructure continue to reshape how energy is produced, stored, and consumed.

Yet behind this transition lies a critical constraint: renewable energy systems continue to depend heavily on a set of metals, brining into question the sustainability of this progress. These critical minerals are essential for batteries, electrical transmission, and grid stability, and yet global demand for these materials is far outpacing its supply.

This imbalance presents an uncomfortable situation; either land-based mining output must increase dramatically, which means accepting severe environmental and humanitarian consequences, or the energy transition slows, prolonging our dependence on fossil fuels [1,2]. Neither outcome should be considered acceptable. Deep-sea mining, while less discussed, offers a third path; one with the potential to secure the raw materials required for electrification without scaling the most damaging aspects of land-based extraction [3].

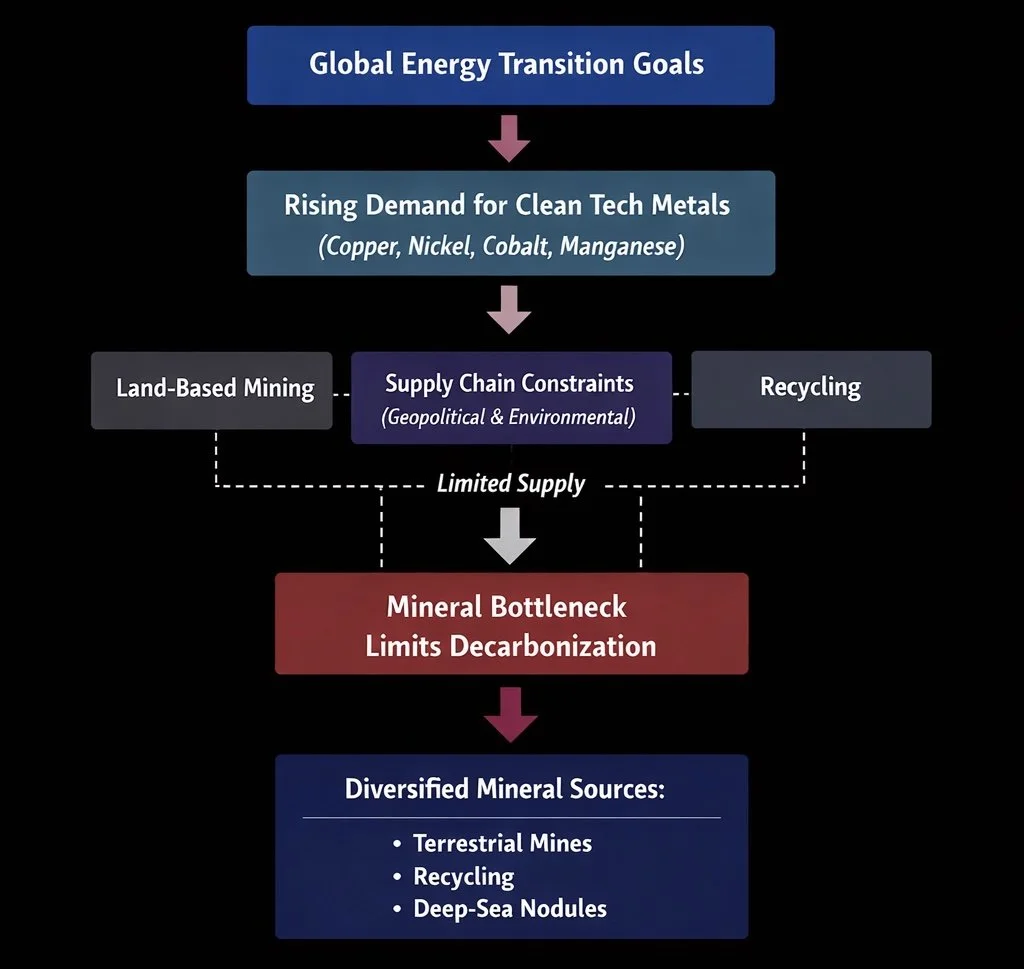

Figure 1. The global energy transition is increasingly constrained by access to critical minerals. Rising demand for copper, nickel, cobalt, and manganese places pressure on existing supply chains, creating a mineral bottleneck that limits decarbonization and necessitates diversified sources, including recycling and deep-sea polymetallic nodules.

1.0 Critical Minerals and Their Role:

1.1 Cobalt:

Cobalt continues to remain one of the most controversial materials in the modern energy economy. Most of the current global production of cobalt originates in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where there are little-to-no labor protections and extraction practices continue to devastate the local environment [4]. Despite these concerns, cobalt demand continues to rise due to its crucial technical role in lithium-ion batteries.

In nickel–manganese–cobalt (NMC) cathodes, cobalt improves the structural stability of the battery, which in turn enhances cycle life while also reducing degradation over time. So, while cobalt is often associated with thermal runaway risks, its controlled use improves overall thermal stability within modern battery designs. Because of this, cobalt remains difficult to eliminate entirely without sacrificing overall performance or the longevity of a battery [5].

1.2 Copper:

Copper is the backbone of electrification, as without it, efficient transportation of energy would be impossible. This is due to copper’s high electrical conductivity, which makes it irreplaceable for power transmission, renewable energy infrastructure, and electric motors. Every wind turbine, solar array, charging station, and transmission line relies on copper to function efficiently as it does a great job of moving electricity around [6].

While recycling contributes meaningfully to copper supply, mining remains the dominant source for sourcing copper [7]. And so, as electrification expands globally, the demand for copper is only expected to increase substantially, placing long-term strain on existing mines and their surrounding environment [8]

1.3 Manganese:

The role manganese plays in modern energy storage systems is lesser known, yet vital. Within battery cathodes, manganese helps stabilize the crystal lattice, which is the rigid atomic framework that hosts and guides the movement of lithium ions during charging and discharging. This lattice structure must remain intact through thousands of charge–discharge cycles; if it degrades, the battery’s ability to store energy diminishes over time. By reinforcing lattice stability, manganese reduces capacity fade and improves long-term reliability. As batteries are increasingly deployed in grid-scale applications where long service life and structural durability are essential—manganese’s importance will continue to grow [9].

1.4 Nickel

Nickel is the metal leading the modern energy revolution, due to it possessing an extremely high energy storage capacity. This feature makes Nickel essential in batteries and modern energy storage systems, as it enables longer driving ranges in electric vehicles and higher-capacity energy storage systems [10]. Nickel-rich cathodes dominate both NMC and nickel–cobalt–aluminum (NCA) chemistries and typically represent the largest fraction of cathode material as shown in Table 1. Manufacturers continue to push and strive for higher performance and longer range, creating a demand for nickel that is accelerating faster than nearly any other battery metal.

Table 1. Summary of Critical Minerals

| Mineral | Primary Role in Energy Systems |

Major Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Cobalt | Stabilizes battery cathodes; improves longevity and thermal stability |

NMC batteries in electric vehicles, grid-scale energy storage |

| Copper | Conducts electricity efficiently |

Wiring, inverters, connectors for renewable energy grids, EVs |

| Manganese | Maintains cathode lattice structure; prevents capacity fading |

NMC batteries, long-life energy storage systems |

| Nickel | High energy density; enables long-range energy storage |

NMC and NCA batteries in electric vehicles, large-scale storage |

These four minerals collectively underpin modern renewable energy systems, with demand trajectories that are both steep and accelerating. Today, their supply chains are fragmented and often highly concentrated, creating critical bottlenecks for each metal individually. In contrast, all four occur together in polymetallic nodules on the deep-sea floor, making them uniquely valuable as a consolidated resource.

2.0 Macro-Level Applications:

2.1 Energy Generation and Transmission

Current sources of renewable energy, such as wind, solar, and hydroelectric power all rely on copper-intensive infrastructure for energy transportation. Many large-scale wind farms, particularly offshore installation, require an extensive amount of cabling, transformers, and subsea transmission lines in order to deliver electricity to population centers. Without an adequate copper supply, the capacity of renewable energy generation cannot scale effectively, delaying its integration into modern energy grids.

2.2 Energy Storage and Grid Stability

Modern power grids are evolving from what they once were. Historically, electricity mainly flowed in one direction, and that was from centralized power plants to consumers. Yet today, grids must be able to accommodate unevenly distributed power generation, intermittent supply, and dynamic demand as energy consumption trends have changed [11], while also having new sources feed into them.

One of the primary components to this shift is battery energy storage systems (BESS), and they operate differently depending on what level they are at. At a residential level, these systems, such as home batteries (often referred to as powerwalls), are able to store excess solar energy that was generated during daylight hours and later release it during periods of peak demand or grid outages [12]. This emerging system is able to reduce household reliance on fossil-fuel-based peaker plants, which improves overall local grid resilience.

Yet at a utility scale, they behave differently, as grid-connected battery farms perform several critical functions [13]:

Load balancing: absorbing excess renewable energy during low demand and discharging during peak demand

Frequency regulation: stabilizing grid voltage and frequency in real time

Grid resilience: providing backup power during outages or transmission failures

A few decades ago, large-scale battery storage systems were largely theoretical, but today they are actively deployed around the world, such as in Chile, to stabilize renewable-heavy grids [14]. While earlier systems and some current deployments relied on nickel-, cobalt-, and manganese-based chemistries such as NMC, the majority of new grid-scale projects now favor lithium-iron-phosphate (LFP) batteries due to their lower cost, longer cycle life, and improved safety. Emerging alternatives—including sodium-ion and flow batteries—are also beginning to play a role, meaning that a secure and diversified supply of key battery materials remains important for modern grid reliability [15].

Without large-scale battery storage, renewable energy remains constrained by intermittent production, leading to the loss of terawatt-hours (TWh) of electricity each year and billions of dollars in unrealized revenue [16]. Batteries address this challenge by converting renewable generation from intermittent availability into dispatchable power that can be delivered when demand requires it.

3.0 Why These Minerals Matter:

Fossil fuels currently account for 68% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions, and nearly 90% of total carbon dioxide emissions [17]. If we continue along this trajectory, we will only further destabilize the climate and intensify the environmental damage that is already taking place.

Renewable energy technologies have been around for decades, and they are now mature enough for global deployment; but critical mineral supply has emerged as the bottleneck preventing its full implementation. Meeting projected demand through land-based mining alone would require massive expansions in extraction, compounding environmental destruction and geopolitical risk.

According to the International Energy Agency, insufficient access to critical minerals could slow renewable adoption or prolong fossil fuel dependence, which will only exacerbate the climate disaster [2]. Scientists have agreed that while warming can no longer be stopped completely, minimizing the amount the planet is warmed is imperative for mitigating the possible disaster. And so neither outcome aligns with climate goals or long-term energy security.

Deep-sea mining offers a potential alternative: highly concentrated mineral deposits containing multiple critical elements in a single source. While it requires careful regulation and technological rigor, it may reduce the need for widespread terrestrial mining expansion.

Securing these minerals is not optional—it is foundational to achieving decarbonization at scale.

Conclusion:

Critical minerals form the physical backbone of the global energy transition. From power generation and transmission to storage and grid stabilization, modern renewable systems depend on reliable access to these materials. Current supply chains are increasingly strained, and without alternative sources, this strain will only continue to intensify. The option of deep-sea nodules represents a concentrated, multi-metal resource that could play a decisive role in enabling global electrification.

If we continue to try to solve mineral supply constraints through incremental or insufficient solutions, the energy transition risks slowing, which leaves societies more exposed to the accelerating impacts of climate change, especially impoverished communities. Deep-sea mining, while still emerging and requiring rigorous environmental scrutiny, represents a potential pathway that warrants serious evaluation as part of a broader, diversified mineral strategy.

References:

[1] Earth.Org, “Cobalt mining in the Congo,” Earth.Org. [Online]. Available: https://earth.org/cobalt-mining-in-congo/. Accessed: Dec. 10, 2025.

[2] International Energy Agency, “The role of critical minerals in clean energy transitions: Executive summary,” IEA, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.iea.org/reports/the-role-of-critical-minerals-in-clean-energy-transitions/executive-summary. Accessed: Dec. 19, 2025.

[3] Institute for Energy Research, “Deep-sea mining of critical minerals for EV battery production,” Institute for Energy Research, n.d. [Online]. Available: https://www.instituteforenergyresearch.org/renewable/deep-sea-mining-of-critical-minerals-for-ev-battery-production/. Accessed: Dec. 5, 2025.

[4] U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of International Labor Affairs, 2022 Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor: Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/ILAB/child_labor_reports/tda2022/Congo-Democratic-Republic-of-the.pdf. Accessed: Dec. 22, 2025.

[5] B. Chu et al., “Cobalt in high-energy-density layered cathode materials for lithium-ion batteries,” Journal of Power Sources, vol. 544, 2022, doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2022.231873.

[6] A. F. Soares, R. G. Spers, and R. de O. S. Jhunior, “Projection of global copper demand in the context of energy transition,” Resources Policy, vol. 103, 2025, doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2025.103109.

[7] BHP, “How copper will shape our future,” BHP Insights, Sep. 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.bhp.com/news/bhp-insights/2024/09/how-copper-will-shape-our-future. Accessed: Dec. 28, 2025.

[8] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, “TENORM: Copper mining and production wastes,” EPA, n.d. [Online]. Available: https://www.epa.gov/radiation/tenorm-copper-mining-and-production-wastes. Accessed: Dec. 14, 2025.

[9] R. K. Pachauri et al., “Energy, resources and the environment: Deep decarbonization pathways,” Sustainable Energy & Fuels, vol. 2, no. 6, pp. 1256–1270, 2018, doi:10.1039/C8SE00157J.

[10] P. Dilshara et al., “The role of nickel (Ni) as a critical metal in the clean energy transition: Applications, global distribution, production–demand balance and phytomining,” Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, vol. 259, 2024, doi:10.1016/j.jseaes.2023.105912.

[11] Energy Central, “Balancing the grid: Unbalanced load flow and why it is important,” Energy Central, n.d. [Online]. Available: https://www.energycentral.com/intelligent-utility/post/balancing-grid-unbalanced-load-flow-and-why-it-important-GymwlXA5Y6nMMn6. Accessed: Dec. 3, 2025.

[12] Elsevier, “Battery energy storage,” ScienceDirect Topics, n.d. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/engineering/battery-energy-storage. Accessed: Dec. 23, 2025.

[13] C. Zhao, P. B. Andersen, C. Træholt, and S. Hashemi, “Grid-connected battery energy storage system: A review on application and integration,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 182, 2023, doi:10.1016/j.rser.2023.113400.

[14] International Trade Administration, “Chile energy storage market,” U.S. Department of Commerce, n.d. [Online]. Available: https://www.trade.gov/market-intelligence/chile-energy-storage. Accessed: Dec. 17, 2025.

[15] S. Evro et al., “Navigating battery choices: A comparative study of lithium iron phosphate and nickel manganese cobalt battery technologies,” Future Batteries, vol. 4, 2024, doi:10.1016/j.fub.2024.100007.

[16] Utility Dive, “The era of free excess renewable energy is over,” Utility Dive, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.utilitydive.com/news/the-era-of-free-excess-renewable-energy-is-over/804471/. Accessed: Dec. 30, 2025.

[17] United Nations, “Causes and effects of climate change,” United Nations, n.d. [Online]. Available: https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/science/causes-effects-climate-change. Accessed: Dec. 11, 2025.