The Clarion-Clipperton Zone Explained – Geology, Georesources, Governance & Global Stakes

Introduction:

In the Pacific Ocean lies a region that is becoming increasingly central to global geopolitics and industrial strategy. Measured not just in monetary terms but in long-term consequence, this area has the potential to reshape critical mineral supply chains for decades to come.

The Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) is one of the most unique regions on Earth. It is defined by its vast abundance of polymetallic nodules, but also by the fragile and poorly understood ecosystems that exist within it [1]. Due to its extreme depth and remoteness, this environment has historically been difficult to study, leaving major knowledge gaps that now sit at the center of an intensifying global debate.

Each year, increasing amounts of capital, research effort, and political attention are directed toward the CCZ due to the content of polymetallic nodules. Despite growing urgency to access more critical minerals, no definitive agreement has been reached on how this region should be governed or utilized. That uncertainty carries consequences far beyond this patch of ocean, affecting global supply chains, environmental governance, and international power dynamics.

Understanding the CCZ is, in many ways, understanding modern geopolitics. Examining both the perspectives of ocean scientists and environmental groups, as well as those of governments and companies interested in its resources, provides a clearer view of what is truly at stake.

1.0 A Dive into the Clarion-Clipperton Zone

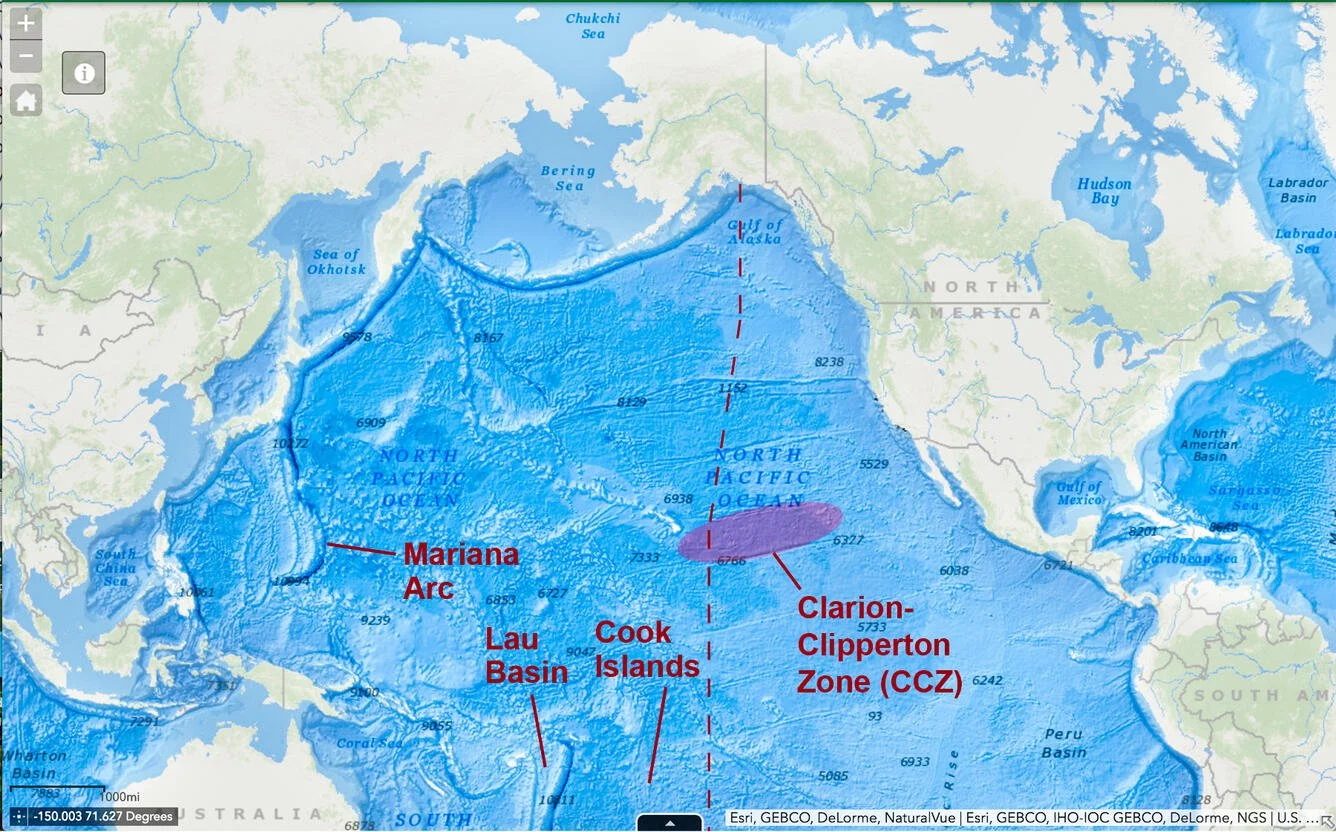

The CCZ is a vast region of the Pacific Ocean spanning approximately 4.5 million square kilometers, roughly half the size of the continental United States. It is bounded by two major undersea geological features: the Clarion and Clipperton Fracture Zones, long east-west-trending structures formed by tectonic activity along the ocean floor [2].

Fig. 1. Map of the Clarion–Clipperton Zone.

Source: U.S. Geological Survey (USGS).

Interest in the CCZ is driven primarily by the presence of polymetallic nodules, rocky concretions rich in manganese, nickel, cobalt, and copper. These nodules were first discovered during the HMS Challenger expedition in the late 19th century [3], but technological limitations prevented serious consideration of commercial extraction for decades.

Advancements in seabed mapping and deep-ocean technology during the 1960s and 1970s renewed interest in the region. Today, estimates suggest the CCZ contains approximately 21.1 billion tons of polymetallic nodules, with an estimated in-situ value of roughly $16.8 trillion [4]. While these figures are imprecise, they illustrate the scale of the resource and the reason for sustained international attention.

Despite this potential, the CCZ remained largely dormant for much of the 20th century. The technical challenges of operating at extreme depths, combined with unresolved legal and regulatory frameworks, made commercial activity impractical.

That has changed. Interest in the CCZ is now at its highest point in history. Multiple ventures are actively developing technologies aimed at commercial extraction. However, no full-scale operations have begun. While environmental and technical challenges remain significant, the primary barrier has been regulatory uncertainty. For most companies, progress is effectively stalled until a formalized international “rulebook” for deep-sea mining is established.

2.0 The Global Stakes

The significance of the Clarion-Clipperton Zone extends well beyond the monetary value of its resources. The minerals contained within the CCZ are foundational to modern technologies. Renewable energy systems, electric vehicles, advanced batteries, and defense technologies all rely on steady access to these materials [13].

At present, critical mineral supply chains are highly concentrated. China plays a dominant role not only in mineral sourcing but also in downstream refining and processing. As geopolitical tensions rise, reducing dependency on concentrated foreign supply chains has become a strategic priority for the United States and its allies [14]. Control over these resources therefore carries implications that are economic, technological, and geopolitical. The CCZ represents one of the few remaining large-scale opportunities to alter that balance.

3.0 The Political and Legal Framework Governing the CCZ

The CCZ contains enough nodules to alter to global supply chain of critical minerals, meaning debate around it is natural, primarily the debate centers around the legal framework governing the CCZ. Two primary legal structures shape the current debate surrounding the Clarion-Clipperton Zone.

3.1 The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) was adopted in 1982 and entered into force in 1994. It functions as the foundational legal framework governing maritime activity, defining maritime zones, navigation rights, and resource management across the world’s oceans [5].

For deep-sea mining, UNCLOS is particularly relevant because the CCZ lies in international waters. Several articles address activities in these areas, but Article 136 is central, declaring that “the Area and its resources are the common heritage of mankind.” This principle underpins the international approach to seabed governance and places deep-sea resources beyond the sovereign control of any single nation [6].

3.2 The Deep-Sea Hard Minerals Resources Act (DSHMRA)

In contrast, the United States operates under the Deep-Sea Hard Minerals Resources Act (DSHMRA), enacted in 1980 as an interim domestic framework for regulating U.S. deep-sea mining activities prior to the establishment of an international regime [7].

Because the United States has never ratified UNCLOS, DSHMRA remains in force. Under this act, licensing and regulatory oversight for U.S.-based exploration and extraction activities are administered by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) [8].

4.0 The Global Conversation

UNCLOS’ designation of deep-sea resources as the common heritage of mankind has made the development of a workable mining framework slow and contentious. The system that emerged allows developing nations to sponsor private contractors, not because these states necessarily possess the technical means to exploit the seabed, but to prevent deep-sea resources from being monopolized by wealthy, technologically advanced countries [9].

Through this sponsorship model, the International Seabed Authority (ISA) aims to preserve equitable access while pairing capital and technical capability with state-level oversight. However, environmental concerns have significantly slowed progress toward a finalized mining code. Critics argue that the ecological impacts of deep-sea mining are insufficiently understood and that irreversible harm could occur if commercial operations begin prematurely [10]

As of 2026, the ISA has yet to ratify a comprehensive exploitation framework. This delay has fueled frustration among some member states, particularly in the Pacific.

In June 2021, the island nation of Nauru invoked the so-called “two-year rule” under UNCLOS on behalf of its sponsored contractor, Nauru Ocean Resources Inc. (NORI), a subsidiary of The Metals Company. This action formally required the ISA to finalize mining regulations within two years. That deadline passed in 2023 without a completed code, further intensifying debate and uncertainty [11].

While international progress has stalled, the United States moved unilaterally. In April 2025, the Trump administration issued Executive Order 14285, directing NOAA to streamline the permitting process for both exploration and commercial extraction under DSHMRA [12]. The response was swift. The ISA raised concerns that the order undermined international seabed governance, while China, several Pacific states, EU-aligned governments, and environmental organizations criticized the move as a violation of multilateral norms.

Although no immediate legal action followed, the diplomatic backlash framed the executive order as a direct challenge to the UNCLOS framework. It highlighted a growing fracture between international consensus-based governance and national approaches driven by strategic urgency. The legality of deep-sea mining now sits in a gray zone. Without an ISA-ratified mining code, unilateral action by individual states appears increasingly likely as companies seek clearer regulatory pathways.

Conclusion

The Clarion-Clipperton Zone is more than a remote region of the Pacific Ocean. Its value lies in the convergence of environmental uncertainty, strategic necessity, and unresolved governance. The decisions made, or deferred, regarding the CCZ will shape global resource access, environmental precedent, and international cooperation for decades.

Deep-sea mining remains fraught with unknowns, but prolonged regulatory inaction is itself a decision with consequences. By establishing a clear and responsible framework, the International Seabed Authority has the opportunity to define how humanity approaches resource extraction in the global commons.

This is no longer a question that can be postponed. The minerals contained within the CCZ sit at the intersection of climate transition, industrial resilience, and geopolitical stability. How the world chooses to govern this region will set a precedent that extends far beyond the ocean floor.

Citations:

[1] C. R. Smith et al., “Editorial: Biodiversity, connectivity and ecosystem function across the Clarion-Clipperton Zone: A regional synthesis for an area targeted for nodule mining,” Frontiers in Marine Science, vol. 8, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/marine-science/articles/10.3389/fmars.2021.797516/full

[2] The Pew Charitable Trusts, The Clarion-Clipperton Zone, Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Online]. Available: https://www.pew.org/~/media/assets/2017/12/sea_the_clarion_clipperton_zone.pdf

[3] International Seabed Authority, “Exploration contracts.” [Online]. Available: https://isa.org.jm/exploration-contracts/

[4] I. Epikhin et al., “Seabed mining: A $20 trillion opportunity,” Arthur D. Little, Viewpoint Report. [Online]. Available: https://www.adlittle.com/en/insights/viewpoints/seabed-mining-20-trillion-opportunity

[5] International Maritime Organization, “United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.” [Online]. Available: https://www.imo.org/en/ourwork/legal/pages/unitednationsconventiononthelawofthesea.aspx

[6] United Nations, United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, 1982. [Online]. Available: https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf

[7] National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Global Critical Issues in Deep-Sea Hard Mineral Resources Activities: Summary, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.noaa.gov/sites/default/files/2025-08/gcil_dshmra_summary.pdf

[8] National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), “Deep seabed mining.” [Online]. Available: https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/deep-seabed-mining/

[9] S. Robb et al., “Effective control and state sponsorship in deep seabed mining,” Marine Policy, vol. 169, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0025326X24010968

[10] H. J. Niner et al., “Deep-sea mining with no net loss of biodiversity—An impossible aim,” Frontiers in Marine Science, vol. 5, 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/marine-science/articles/10.3389/fmars.2018.00053/full

[11] P. Singh, “The two-year deadline to complete the International Seabed Authority’s mining code: Key outstanding matters that still need to be resolved,” Marine Policy, vol. 138, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0308597X21004152

[12] The White House, “Unleashing America’s offshore critical minerals and resources,” Presidential Action, Apr. 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/04/unleashing-americas-offshore-critical-minerals-and-resources/

[13] International Energy Agency, “Critical minerals.” [Online]. Available: https://www.iea.org/topics/critical-minerals

[14] Council on Foreign Relations, Leapfrogging China’s Critical Minerals Dominance. [Online]. Available: https://www.cfr.org/reports/leapfrogging-chinas-critical-minerals-dominance